9 Child Welfare Policy

As the usage of residential and day schools started to decrease in the 1950s and 60s, the child welfare system became the primary mechanism for colonization and assimilation. The “Sixties Scoop” is a term that describes a process where Indigenous children were taken away from their families and put into Euro-Canadian homes. Although the result of the Indigenous child welfare policy during this time was assimilatory, the motivation of provincial child service agencies was much less overtly racist than the Federal Indian Affairs Department.

CBC News – The Sixties Scoop Explained. Sept. 29, 2016.

Many of the children who were apprehended during the Sixties Scoop were the offspring of residential school survivors who were not able to effectively care for a child. Intergenerational trauma played a role in the Sixties Scoop and still plays a role in Indigenous child welfare today. With that said, most of the time children were removed for no other reason than poverty.[1]

Prior to 1960, about 1% of children in the care of government child services were Indigenous. By 1973, that number jumped to 30-40% despite Indigenous children making up only 4% of the general population.[2] From 1965 to 1981, the number of Indigenous children transferred into the care of non-Indigenous families increased by 250%.[3] Between 1960 and 1980, the Indian Affairs Department reports 11,000 Indigenous children were adopted, but due to privacy laws around adoption that number is likely much higher.[4] About 70% of those children were adopted into non-Indigenous families.[5] Furthermore, Metis people were not even recognized as distinct people until 2016.[6] As a result, many more Metis were put into government custody early on and their removal would not be accurately reported.[7]

Due to legislative changes in 1951, the provinces gained the ability to administer child and family services on-reserve. When the legislative changes were made Indigenous communities, especially on-reserve, were dealing with the repercussions of a century of discriminatory laws that put First Nations peoples in a position of extreme socio-economic disparity. Instead of providing community supports the government’s response was to take the children away and put them into non-Indigenous homes.

The proportion of Indigenous children in care has not changed drastically since that time. According to a census done in 2016, 7.7% of children in Canada are Indigenous, yet 52.2% of children in care are Indigenous.[8] Understanding the legislative and funding regimes that led to the Sixties Scoop is still relevant and can help understand why these problems persist.

As mentioned previously, legislative changes were made to the Indian Act in 1951 which led to the Sixties Scoop. The amendment in question is section 88, which gives provincial laws general applicability over ‘Indians’.[9] The law is as follows,

88. Subject to the terms of any treaty and any other Act of the Parliament of Canada, all laws of generally application from time to time in force in any province are applicable to and in respect of Indians in the province, except to the extent that such laws are inconsistent with this Act or any order, rule, regulation or by-law made thereunder, and except to the extent that such laws make provision for any matter for which provision is made by or under this Act.[10]

Section 88 is unique because it unilaterally gives the provinces jurisdiction over something that falls under the federal responsibility in the division of powers (91(24)).[11]The section raises multiple constitutional questions that have been litigated extensively since its adoption.[12] For our purposes, we just need to know that the effect of the section was to extend provincial laws of general application onto Indians living on reserve. Since it was previously the federal government’s responsibility to enact legislation that specifically dealt with Indigenous peoples, the provinces were not prepared to deal with it.

Not only were provincial child welfare agencies ill-prepared to deal with culturally sensitive issues, but their child welfare strategies also conflicted with aspects of the Indian Act. The federal government had created a status regime where there was a multitude of ways a person could lose status. For example, women would lose their Indian status if they married someone who was a non-Indian or not a registered Indian. If they had a child with a non-status person then their child would be non-status, and illegitimate children would also be non-status.[13] There was also a section in the Indian act that prohibited non-status people from living on the reserve. These laws were not changed until 1985 when Bill C-35 was passed.

The status regime of the ’50s and ’60s contributed to the separation of families and also made it hard for provincial child service agencies to provide adequate services due to conflicts. For instance, provincial child service agencies tend to rest legal custody of children with their mothers, but the Indian Act said that a child gained status through the father. If a single-status mother could not prove that the father was status, then the child would be non-status and could not live on the reserve.[14] The inability for non-status Indians to live on the reserve also made it so social workers could not relocate a disenfranchised child to live with family members living on reserve.

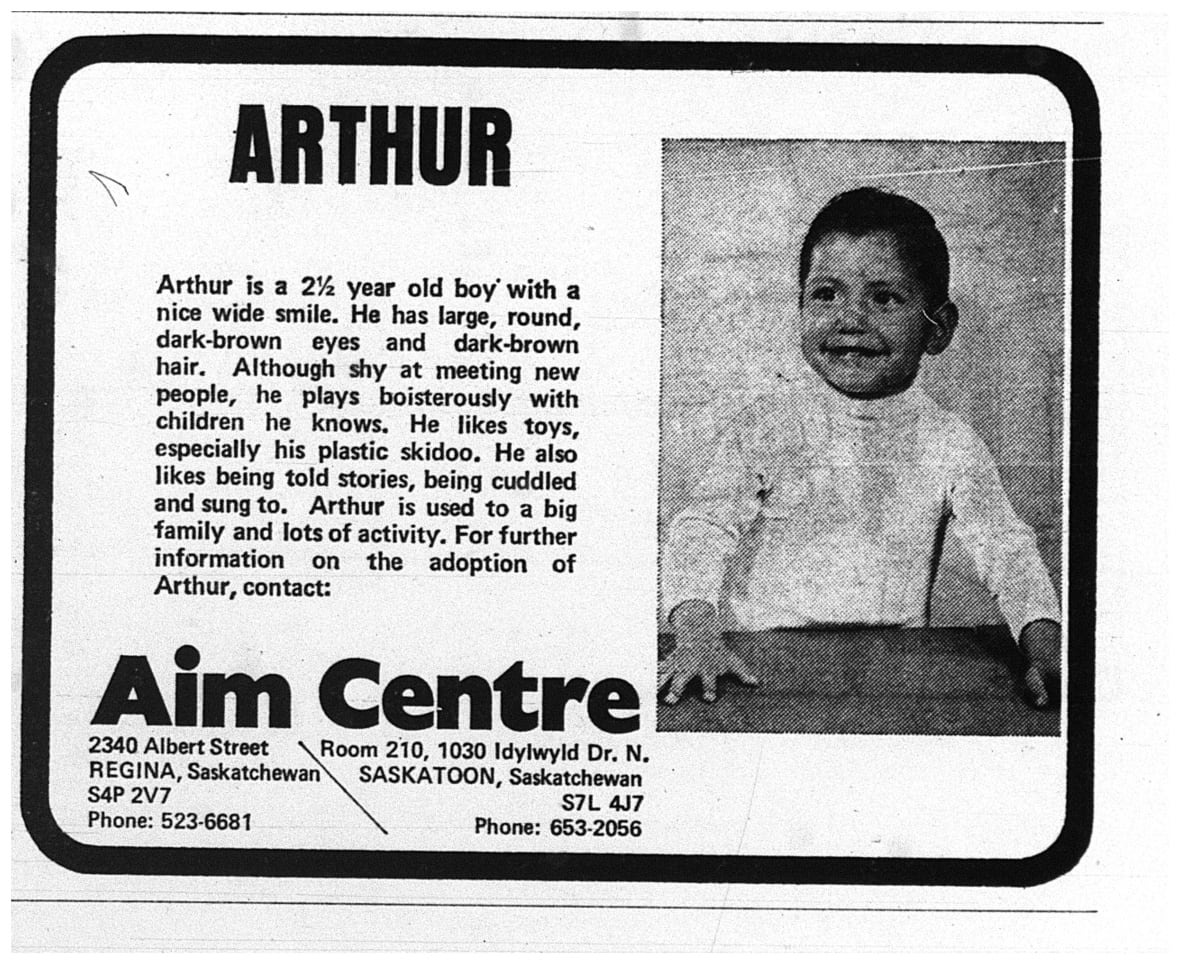

The racial integration policy of the Indian Act combined with the increased number of children-in-care put provincial agencies in a tough position and led to some questionable policy choices. One example is the “Adopt Indian and Metis project” (AIM) in Saskatchewan. It was only a two-year pilot project conducted by the provincial child welfare agency but reflected a wider societal conception of the benefits of assimilation. AIM created an advertising campaign that would promote the adoption of Indigenous children into non-Indigenous families.

Adoption is preferred by social service agencies because it provides children with a long-term home and is also much cheaper than foster programs. The problems from transracial adoption in the case of status-Indians are that it divides communities and separates children from their culture, as well as raises some constitutional issues in respect to status-Indians.[15]

The courts used notions of equality to justify the adoption of status Indians into non-Indigenous homes, in turn promoting culturally insensitive child welfare policy. The AIM program is just one example of a patchwork of child welfare programs throughout the country. Every province has different laws around child welfare making it harder for the provinces and the federal government to have a unified response. The federal government was also reluctant to provide extra funding to the provinces to support the provinces.

- Fournier, S., & Crey, E. Stolen from our embrace. (Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre. 1997) ↵

- Marie Adams, Our Son, A Stranger: Adoption Breakdown and its Effect on Parents. (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2002) University Press (2002) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Raven Sinclair et al, Wicihitowin, (Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing 2009) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Daniels v. Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development), 2016 SCC 12 ↵

- Margaret Ward, The Adoption of Native Canadian Children (Ontario: Highway Book Shop, 1984) ↵

- Government of Canada, Reducing the Number of Indigenous Children in Care, <www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1541187352297/1541187392851> [perma.cc/RA3J-ZC4U]. ↵

- <www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sixties-scoop#:~:text=The%20department%20of%20Indigenous%20Affairs,were%20removed%20from%20their%20homes> [perma.cc/CJ9S-6DN6] ↵

- Indian Act R.S.C. 1985, C. I-5 ↵

- Kerry Wilkins. “Still Crazy After All These Years Section 88 of the Indian Act at Fifty." (2000), 38:2, Alta. Law Rev., 458) <www.canlii.org/en/commentary/doc/2000CanLIIDocs144#!fragment/zoupio-_Toc3Page3/BQCwhgziBcwMYgK4DsDWszIQewE4BUBTADwBdoAvbRABwEtsBaAfX2zgGYAFMAc0I4BKADTJspQhACKiQrgCe0AORLhEQmFwIZcxSrUatIAMp5SAIUUAlAKIAZGwDUAggDkAwjeGkwAI2ik7IKCQA> [perma.cc/7N95-YBDG]. ↵

- Dick v R, R. v. Alphonse, R. v. Kruger and Manuel, ↵

- Martin Canon. Men, Masculinity, and the Indian Act (Vancouver, UBC Press, 2019) ↵

- Stevenson, Intimate integration: A study of aboriginal transracial adoption in Saskatchewan, 1944-1984, (Saskatoon, University of Saskatchewan, 2015) At page 3. ↵

- Natural parents V. Superintendent of Child Welfare et al. (1976) 2 SCR 751 ↵