11 History of Trauma

The above timeline offers a linear representation of the traumas that Indigenous Peoples in Canada continue to address today. Sources of these traumas, as explained below, include the residential school system, attendance at residential school as day scholars, the federally-operated day schools, and the 60s Scoop.

Residential Schools

https://media.tru.ca/id/0_b8enpd1n?width=608&height=402&playerId=23451100

Kamloops Indian Residential School survivor, Elder Eric Mitchell, shares good and bad memories from his time at KIRS. Originally recorded at the 1L TRC Day, January 31, 2019 on site, in Moccasin Square Gardens (MSG), the restored and functional gymnasium of the KIRS.

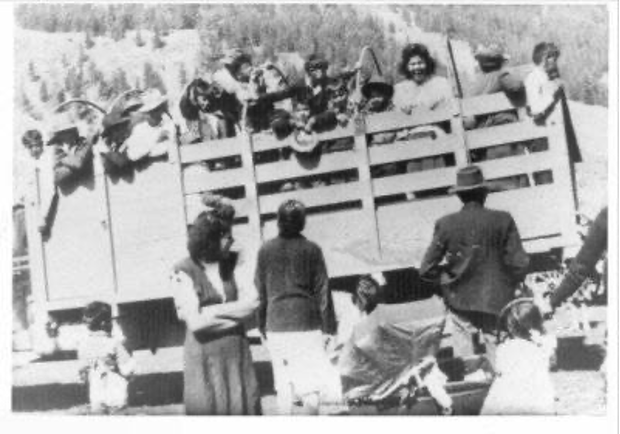

Indigenous Peoples had traumatic experiences due to the residential schools, even if they did not attend themselves. Many accounts of the residential school experience begin with children being taken from their families via Indian agents or even cattle cars arriving on the Indian reserve to collect children along the route to the school.[1] Many parents tried to fight to keep their children at the risk of serious repercussions such as fines or imprisonment.[2] Some lobbied the government for better schools closer to home and others took more drastic measures like hiding their children or sending them away when they knew it was time for them to be collected. Many children returned home either unable to speak their own Indigenous language or fearing practicing their customs.[3]

Within residential schools, children faced the loss of their culture and identity, starvation, abuse, illness, a lack of proper medical care, and other mistreatment. In addition, those who attended residential schools have overwhelmingly expressed an atmosphere of fear and loneliness in a place where they were deprived of affection and approval.[4] Many students learned to hide the truth and say only what they knew was appropriate, what they knew those in charge wanted to hear. They learned to lie as a survival technique. For others, they learned they could exploit weakness for their own survival. Children received very little actual education within the schools, sometimes as little as 3 hours a day. The remainder of their time was spent in church or other religious education or working to aid in the running of the school. This took various forms such as general labour, sewing, cooking and cleaning.

Due to the treatment of the children in the residential schools and the lack of affection or relationships with their caregivers, children who grew up in the residential school system often struggled with parenthood later in their lives. Many children of parents who had gone to residential school received little affection from their own parents. Survivors have described this carrying over not only into parenthood, but into all aspects of their lives. Many describe being distant or unable to express their feelings or form bonds with their family and friends, even believing that their distance extends to their grandchildren. [5] One survivor spoke about his inability to hug or comfort his children and his inability to get close to someone in a relationship. He stated that he couldn’t tell his children that he loved them because showing affection like that seemed unnatural.[6] Others, suffering from the trauma of their experiences turned to other means of coping including alcohol, drugs and suicide. This has led to not only traumatic circumstances for them and their families, but also to stereotyping, racism and judgement that persists today.

Survivor Story

Me and my brother, M. were playing outside when a lady, I think she was a nurse, came. I saw a car come into the yard and didn’t think nothing of it and my mom called us. M. and I went running over there and she just said “get in the back of the car”. They drove us into town and we sat in a hallway and waited.

When this lady and my grandmother, M.C. came out, M. just grabbed me and I just grabbed him because we heard them saying that M. had to go to Tranquille [which at the time was a Tuberculosis Sanatorium] and I was going the other way they had a hard time taking us apart and when we got downstairs there were two taxis. The lady went with M. and my mom came with me. I didn’t know where I was going but I knew I wasn’t going to see M. again.

When they took him away they brought me to the residential school. I didn’t know where I was going, I didn’t understand what was going on and I kept asking my mom what she was doing. Then when we got to that building over at the residential school, the front building and they walked us in she just said “you have to go” she wouldn’t look at me, she just looked straight ahead and said “you have to go and your brother has to go” and then when we got to the residential school I didn’t understand and then the nuns came and I looked at my mom and she just kept telling me “you have to go”.

I didn’t know where I was going. I remembered going downstairs and saw all these girls. Then they brought me in this one room and I had really long hair and the lady, it was a nun, she said we all had to shower and I guess they were telling me how much I stink. Then they grabbed my hair and they told me to sit on a stool so I sat on it and then they started cutting my hair and I didn’t know what was going on. I was really scared, I didn’t know why they were cutting my hair. I was really embarrassed because they said that I stink. They took me where the bathroom was the lady bathed me and they told me my number was 13 that’s when they gave me my number and clothes.

I was in there for two years in grade one, because I didn’t understand. They always got mad at me because I didn’t understand the English language. I didn’t understand what they were saying to me and I had a hard time with that. I just kept quiet because I heard somebody say if you don’t understand just keep quiet. I just kept quiet all the time while I was there until they taught me to speak English. My friends helped me out a lot. If I didn’t understand what they were saying, my friends would help me. They were just little too I don’t know how we all connected we just did.

I met this big tall guy I guess was a loner there. I don’t know what I was doing I was playing in the hallway and he came along and said come here and I just thought oh OK so I followed him when we got to the laundry room he picked me up and put me on one of those things where you fold clothes I didn’t know what was going on my mind was blank and I don’t know if I was scared or numb I just don’t have any feelings nothing inside and he laid me on the table and started to touch started touching me all over and taking my clothes off I didn’t know what was going on and then he told me I wasn’t allowed to tell nobody this continued for a long time.

__

This is a condensed excerpt from Behind Closed Doors. The student told their story anonymously and the other names have been further anonymized this excerpt.[7]

Day Scholars

https://media.tru.ca/id/0_hnirrrf9?width=608&height=402&playerId=23451100

Elder Connie Jules, day scholar survivor from KIRS, shares part of her experience. Originally recorded at the 1L TRC Day, January 31, 2019 on site, in Moccasin Square Gardens (MSG), the restored and functional gymnasium of the KIRS.

Not all students who attended the residential schools lived at the school. There was a group of students who attended but still lived at home. These students were known as the “day scholars”. The day scholars also experienced violence and abuse at the schools like many other students. In addition to this however, they also faced unique abuse at the hands of other students in the form of bullying. Many were bullied by other students since they were privileged enough to be able to go home at the end of the day.[8] Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc continues to seek redress for the day scholars. When former Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology[9] on behalf of the federal government in 2008 to survivors of residential schools, day scholars were not included. When the common experience payment (CEP) process [10]was established as a component of the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, day scholars did not qualify.[11]

Through this dark history lies an opportunity for law students at TRU Law. In partnership between Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, Sechelt, and James Bay Cree, redress is being sought through a certified class action.[12] Unlike the CEP, the day scholar class action is certified on three classes: the survivor class (person who attended federally owned and operated residential school as day scholars), the descendant class (the children of day scholars), and the band class (bands with residential school on or near their lands). The process began in 2010, with a class action suit being filed in Federal Court in 2012, and becoming certified in 2015. The suit was unsuccessful in their 2019 application for advanced costs, Harrington J. noted that day scholar claims “have prima facie merit…rais[ing] issues that transcend their individual interests, [and] are of public importance…”[13] Despite the advance costs application being denied, Harrington J. further noted “[t]he Plaintiffs are dying”[14] due to the length and duration of proceedings, and asked, “Is it [Crown’s] intention to grind these 105 Bands into poverty and bankruptcy before this matter ever proceeds to trial?”[15] In 2020 by order by Barnes J.[16] required Canada to provide database fields and field content for the expected document production of at least 132,000 documents.[17] The issue on application claimed that many of the documents produced by Canada for discovery were of such poor quality that optical character recognition (OCR) technology was unreadable “except by tedious human intervention.”[18]

The importance of the band class is to repair the harm that occurred within the communities themselves. It seeks redress for those interruptions in occupation of tmícw. It is the first of its kind to consider repairing the relationship with the land and the communities themselves. This approach takes into full consideration all quadrants of the Cḱuĺtn, connecting the elements of tmícw (physical), púsmen (emotional), sképqin (mental), and súmec (spiritual/self-actualization).[19]

JG was a Day Scholar at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. Day Scholars had a much more similar experience to Residential School Survivors than many people realize. JG was a fourth-generation attendee of residential schools. She was told by a nun that she was too pretty and that all she would become would be pregnant as a teenager and would amount to nothing. (She now holds multiple degrees). But this stuck with her for a long time. When she attended the school, she felt like she was an immigrant on her own land. The school segregated the residents and the day scholars by only giving certain opportunities to students who lived at the school. JG’s brother had to attend the school, not as a day scholar, but as a resident to be permitted to be on the boxing team. Being a day scholar did not stop students from being physically, mentally and emotionally abused. Neither did community connections. JG was the daughter of a chief and yet she was abused by a priest that was close to her family. She did not tell her story for 50 years. Instead, she carried her guilt for fear that it would bring dishonor to her family. She also didn’t know that her sister was also abused by the same person because it was all believed to be too shameful to share. In addition to what students faced at the hands of the school, the day scholars faced ridicule by the other students. JG stated that other kids would make fun of them and make day scholar seem like a dirty thing to be. JG said that while they didn’t have close friends, the kids that were day scholars stuck together because they were from the same community. They tried to look out for one another. Day Scholars are still suffering due to having to relive this trauma over again through the litigation process that is currently ongoing. JG has spoke at the first year TRC days about her experience as a day scholar.

Sixties Scoop

https://media.tru.ca/id/0_hgfpvxl1?width=608&height=402&playerId=23451100

Sixties Scoop survivor, Dave Manuel from Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc shares part of his experience and navigating his way back to his home community. Originally recorded at the 1L TRC Day, January 31, 2019 on site, in Moccasin Square Gardens (MSG), the restored and functional gymnasium of the KIRS.

The residential school system was not the only attempt by the Canadian government to assimilate Indigenous children. In the mid 20th century, the government began phasing out compulsory attendance at residential schools there was a shift in Indigenous child welfare policy. The result of this shift in policy meant that rather than sending students to residential school, children were apprehended from their families and placed either for adoption or into the foster care system.[20] This is referred to as the “Sixties Scoop” since there was a large-scale removal or “scooping” of Indigenous children from their homes during the 1960s, 70s and 80s.[21]

In 1951, amendments to the Indian Act gave provinces more jurisdiction over Indigenous child welfare. At that time, the detrimental effects of over a century of colonial policies, such as residential schools and Indian reserves, had contributed to Indigenous communities that were under-serviced and under-resourced.[22] Instead of providing community support to enhance child welfare, provincial governments removed Indigenous children from their communities at alarming rates. From 1951 to 1964, the number of Indigenous children in provincial care in British Columbia increased 50 times. The removal of these children was done without the parents’ or bands’ consent, and they were predominantly adopted or fostered out to non-Indigenous families. [23]

Depending on the source, anywhere from 11,132 to 20,000 Indigenous children were adopted out between 1960 and 1990. Tens of thousands more were placed in the foster care system.[24] Some provinces designed specific programs for the adoption of Indigenous children by non-Indigenous families. For example, Saskatchewan’s “Adopt Indian and Metis Project” would feature the removed children in television, radio, and newspaper advertisements to facilitate adoption by non-Indigenous families across North America.[25] Many of these children were also adopted out abroad, further severing their ties to their community and culture. Children were sent across Canada, to the United States, and even as far as Australia and New Zealand. In some years, the percentage of Indigenous children adopted by families abroad was as high as 55%.[26] Adoptees and foster children reported sexual, physical, and psychological abuse. Those who did not experience abuse still had to grow up disconnected from their families and culture.

Many children that were apprehended at birth and adopted did not learn about their heritage until they reached adulthood.[27] Some parents would never see their children again, while others would wait decades to be reunited. The scoop was also multi-generational, beginning in the 1960s and continuing until the change in the child welfare policies of the 1980s. Children who had been “scooped” themselves not only had to deal with the trauma of missing identity but also having their own children taken from them.[28] The disproportionate number of Indigenous children in provincial care persists today. The term “Sixties Scoop” has merely evolved into the “Millennium Scoop”.[29]

Survivors of the Sixties Scoop filed numerous lawsuits and class-action lawsuits. In 2017, the Government of Canada signed an agreement to resolve Sixties Scoop litigation, and in August 2018, the court approved the terms of the settlement agreement. The settlement provides “$500 to $750 million in compensation to status Indian and Inuit peoples who were adopted by non-Indigenous families, became Crown wards or who were placed in permanent care settings during the Sixties Scoop.”[30] This translates to an estimated $25,000 in compensation for class members. In addition, $50 million was provided to establish a foundation to support healing, wellness, and education.[31] Not every Sixties Scoop survivor is eligible to apply for compensation through the settlement. Only status Indian and Inuit peoples can apply, excluding Métis and non-status Indians, even though they were also targets of the Sixties Scoop. Further, children adopted out at a young age may be unaware of their heritage and their eligibility. It places the onus on the survivor to prove where they came from and that they are entitled to status. Many of the adoptive families may have no idea where the child’s home reserve was or what their status registration number is.

The Government of Canada states that they are “working with the Métis National Council, provinces, territories, and plaintiffs toward a fair and lasting resolution for all those affected by this dark and painful chapter in Canadian history.”[32] The Métis National Council has been working to connect Sixties Scoop survivors and share the stories of survivors as part of a healing process. To learn more about this initiative, visit: https://metissixtiesscoop.ca/

To learn more about the Sixties Scoop Settlement, visit: https://sixtiesscoopsettlement.info/

Survivor Story

In September 2015, siblings Betty-Anne, Ben, Esther and Rose met for the first time. They were taken from their mother, MJ when they were babies. Betty-Anne, the oldest at 3 years old when taken in 1962. Esther in 1961, Rose in 1963 and Ben in 1965. It took them 50 years to not only meet, but to find each other. All of the children were taken as infants and placed in homes with white families. When it came time to meet, Betty-Anne lived in Saskatchewan (where they were all born), Ben lived in Alberta, Rose lived in British Columbia and Esther lived in California.

Esther began looking for her siblings after her high school graduation. She wrote letters to the Canadian Government but never received replies.

Betty-Anne was the only one of the four to meet their mother before she passed. Their mother was a survivor of residential school and never went back to her home reserve. She lived in cities and towns and only was with white men (the children hypothesized that this is because of the feeling of racial inferiority of Indigenous Peoples that had been instilled in her in residential school). Despite this, their mother spoke their language. She died before the official apology was given by Prime Minister Harper in 2008.

The siblings met at the Calgary airport and spent the following week in Banff together, learning about Indigenous culture and peoples. Ben remarked that he was afraid to meet the siblings because he felt it would be like walking on eggshells. Later, he remarked that it was very hard to know that there were so many years that they never got to be together as a family and a that there was a lot that they missed out on.

At a museum in Banff, the siblings were taught about some traditional practices and it was incredibly difficult and overwhelming for some of them. None of them had much exposure to Indigenous traditions of any kind growing up. If they did learn about any as adults, they did not practice any.

In a one on one interview, Betty-Anne said she was raised in a good home and that people always told her she was lucky and asked her where she would be now if she hadn’t been taken from her mother, as if wanting her to say that it was a good thing, that her life was better off because she had been taken. She said, “I don’t feel lucky, I feel ripped off”. She spoke about how everything she learned at the museum was brand new to her. She remarked that she knew she had family members that had the skills they learned about, but she didn’t (such as how to tan hides). She felt that at her age she should have the basic skills that she never got the chance to learn.

The siblings discussed the policy of the scoop and how it had the same motivating principles of “killing the Indian in the child” as the residential schools did. The siblings all remarked that, although they knew they were Indigenous, they didn’t know anything more than that. Esther (due to growing up in the United States) said that she didn’t even know the term First Nations until a year prior. They discussed how they were not only survivors of the sixties scoop but also intergenerational survivors of the residential school system.

The siblings plan to meet-up regularly in the future. As Rose discussed in a one on one interview, “We have to work together to find our way, to make our own traditions” she remarked that they had to learn birthdays of not only the siblings but also nieces and nephews and the rest of the family they didn’t know they had. She said that it had to be a conscious effort to keep up with one another and that they would have to work to be a family again. She also stated that this was not a reunion, but a family union.

—

This story has been adapted and put into a written format based on the information within the CBC and National Film Board of Canada Documentary Birth of a Family.

Day Schools

Indian or Federal Day Schools were schools established by the federal Department of Indian Affairs and operated from the mid-1800s until 2000, when the last day school closed. It is estimated that 200,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend these schools, these are in addition to the day scholars who attended residential schools.[33] The day schools were often run by the same religious organizations that ran the residential schools, but the children who attended these schools went home at the end of the day instead of living at the school.[34] While these students were allowed to return home each day, they were still subject to physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. However, those who attended day schools were excluded from the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement.

In 2009, Garry McLean, a day school survivor, initiated a legal action regarding the forced attendance of Indigenous children at day schools. McLean became the lead plaintiff for a class action lawsuit for any former students who attended day school.[35] Unfortunately, in February 2019, McLean died before the day school settlement was approved in 2019.[36] On August 19, 2019, the Federal Court approved a $1.47-billion class-action settlement to compensate harms suffered while attending day schools. Compensation for survivors ranges from $10,000 to $200,000, depending on the level of harm experienced while attending day school. Compensation can only be claimed until the cut-off date of July 13, 2022. The settlement also provided $200 million to create a Legacy Fund, supporting health, wellness, commemoration, language, and cultural projects for survivors.[37]

The settlement would not have been reached without the fierce advocacy of the Representative Plaintiffs. Below, a brief biography of each Representative Plaintiff is provided.

The settlement provided compensation for many day school survivors, but it was flawed. First, the claim form requires survivors to provide information about which school they attended and when.[38] For many, it is difficult to recall the exact years they attended, especially if they have repressed the memories from that time in their life. Second, the form also has the potential to re-traumatize survivors of abuse. In order to qualify for compensation, survivors must detail the specifics of their abuse. If they leave out details due to fear, shame, or memory loss, they may receive less compensation. Lastly, the settlement does not cover all of the day schools that operated in Canada. Only day schools that were established, funded, controlled and managed by the Government of Canada were included in the settlement.[39] If a day school was not entirely run or funded by the Government of Canada, it was excluded. For example, if the school was established and funded by the Government of Canada, but controlled and managed by a provincial government or religious group, then that day school would be excluded. Almost 700 schools are included in the list of eligible day schools[40], while another 680 are excluded.[41]

In the wake of the day school settlement, those who were excluded began fighting for recognition. The Unvalidated Day Schools Society (UDSS) was started by Abe Parenteau and George Munroe, who were forced to attend the Duck Bay Special School, one of the excluded day schools in Winnipeg. In their eyes, the federal government is fully responsible for the harms suffered by children who attended day schools, regardless of whether other organizations took part in the operation or funding of some schools.[42] Cooper Regel was obtained as legal counsel for UDSS, and they are early in the process of having the class certified for a class-action lawsuit.[43]

- Bridget Moran & Mary John, Stoney Creek Woman (Vancouver, Arsenal Pulp Press, 14th ed 2007) Chapter 3 ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The survivors speak : a report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015) 23-30. [The Survivors Speak] ↵

- British Columbia Teachers Federation Project of Heart: Illuminating the hidden history of Indian Residential Schools in BC 5. online: TeachBC <teachbcdb.bctf.ca/permalink/resource517> [perma.cc/L5SE-E7NB] Last Accessed January 25, 2021. ↵

- The Survivors Speak, supra note 2 at 109. ↵

- Jack, Agnes S., and Agnes S. Jack. 2001. Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School. (Penticton. Secwepemc Cultural Education Society / Theytus Books Ltd.) 27 [Behind Closed Doors] ↵

- Ibid at 65. ↵

- Jack, Agnes S., and Agnes S. Jack. 2001. Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School. (Penticton. Secwepemc Cultural Education Society / Theytus Books Ltd.) 61-62 [Behind Closed Doors] ↵

- Farrah Johnson, “Day scholar coordinator recounts experiences in residential school” (21 March 2018), online: TRU Omega <truomega.ca/2018/03/21/day-scholar-coordinator-recounts-experiences-in-residential-school> [perma.cc/4VRE-KYVA]. ↵

- “Indian Residential Schools Statement of Apology – Prime Minister Stephen Harper” (11 June 2008), online (pdf): Government of Canada <www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-CIRNAC-RCAANC/DAM-RECN/STAGING/texte-text/rqpi_apo_pdf_1322167347706_eng.pdf> [perma.cc/W8LD-VEQ8]. ↵

- For more information about CEP and its effectiveness, see “The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement’s Common Experience Payment and Healing: A Qualitative Study Exploring Impacts on Recipients” (2010), online (pdf): Aboriginal Healing Foundation <www.ahf.ca/downloads/cep-2010-healing.pdf> [perma.cc/C6N8-5JUL]. ↵

- “Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement” (8 May 2006), online (pdf): Residential School Settlement <www.residentialschoolsettlement.ca/IRS%20Settlement%20Agreement-%20ENGLISH.pdf> [perma.cc/D94P-MDXN]. ↵

- See “Justice for Day Scholars” online. ↵

- Gottfriedson v Canada, 2019 FC 462 at para 24. ↵

- Ibid at para 48. ↵

- Ibid at para 49. ↵

- Of added interest to TRU Law specifically, Indigenous alumni Cheyenne Neszo clerked for Barnes J. at the Federal Court for the 2019-2020 clerkship period. ↵

- Gottfriedson v Canada, 2020 FC 399. ↵

- Ibid at para 8. ↵

- For additional information about the impact and journey of seeking redress for day scholars, see APTN Nation-to-Nation story coverage here. ↵

- “The Sixties Scoop and Indigenous Child Welfare” (25 January 2021 last visited), online: First Nations and Indigenous Studies Department: University of British Columbia <indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/> [perma.cc/C87V-RHKL]. ↵

- Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair & Sharon Dainard, “Sixties Scoop” (22 June 2016), online: The Canadian Encyclopedia <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sixties-scoop> [Sixties Scoop]. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Allyson Stevenson, “Selling the Sixties Scoop: Saskatchewan’s Adopt Indian and Métis Project” (19 October 2017), online: History Matters <https://activehistory.ca/2017/10/selling-the-sixties-scoop-saskatchewans-adopt-indian-and-metis-project/>. ↵

- Sixties Scoop, supra note 2 ↵

- Ryan Flanagan, “Survivors of the '60s Scoop share stories of displacement in new interactive map” (7 July 2020), online: CTV News <www.ctvnews.ca/canada/survivors-of-the-60s-scoop-share-stories-of-displacement-in-new-interactive-map-1.5014276> [perma.cc/SWQ3-KJFA]. ↵

- This was the case with Ruth Hurst. Ruth was scooped and adopted in 1957. She went on to have 10 children of her own who were all scooped as well. – For more information see Blair Crawford “'The sadness that never goes away': Sixties Scoop survivor battles to be recognized as Indigenous” (11 January 2019), online: Ottawa Citizen <ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/the-past-that-will-never-heal-sixties-scoop-survivor-battles-to-be-recognized-as-indigenous> [perma.cc/V6SV-FZZ3]. ↵

- Erin Hanson, "Sixties Scoop" (accessed on 24 August 2021), online: Indigenous Foundations <https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/>. ↵

- “Are you part of the Sixties Scoop class litigation?” (12 June 2020), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1517425414802/1559830290668>. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jackson Pind, Raymond Mason & Theodore Christou, “Indian day school survivors are seeking truth and justice” (27 October 2020), online: Queen’s Gazette <https://www.queensu.ca/gazette/stories/indian-day-school-survivors-are-seeking-truth-and-justice>. ↵

- “Federal Court Certifies Class Action Seeking Compensation for Indigenous Students Abused at Government-Operated Day Schools” (21 June 2018), online: Gowling WLG <https://gowlingwlg.com/en/insights-resources/client-work/2018/federal-court-class-action-indigenous-school-abuse/>. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Garry McLean, lead plaintiff in Indian Day School class action lawsuit, dead at 67” (19 February 2019), online: Canadian Broadcast Network <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/garry-mclean-dies-1.5025517>. ↵

- “Historic $1.47-Billion Settlement Approved for Survivors of Federal Indian Day Schools and Federal Day Schools” (19 August 2019), online: Gowling WLG <https://gowlingwlg.com/en/insights-resources/client-work/2019/historic-1-47-billion-settlement-day-schools/>. ↵

- “Indian Day Schools Class Action Settlement – Claim Form” (accessed on 24 August 2021), online (pdf): Federal Indian Day Schools Class Action <https://indiandayschools.com/en/wp-content/uploads/indian-day-schools-claim-form-en.pdf>. ↵

- “Are you part of the Federal Indian Day Schools class action” (7 July 2020), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1552427234180/1552427274599#sec2>. ↵

- “Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools” (accessed on 24 August 2021), online (pdf): Federal Indian Day Schools Class Action <https://indiandayschools.com/en/wp-content/uploads/schedule-k.pdf>. ↵

- “Day Schools” (accessed on 24 August 2021), online: APTN National News <https://www.aptnnews.ca/dayschools/>; “Sorting out day schools and claims for compensation on InFocus” (5 February 2020), online: APTN National News <https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/sorting-out-day-schools-and-claims-for-compensation-on-infocus/>. ↵

- “School survivors left out of federal settlement gear up for class-action suit” (14 November 2019), online: APTN National News <https://www.aptnnews.ca/infocus/school-survivors-left-out-of-federal-settlement-gear-up-for-class-action-suit/>. ↵

- “Unvalidated Day Schools” (accessed on 24 August 2021), online: Cooper Regel North <https://www.cooperregelnorth.ca/class-action-cases/unvalidated-day-schools/>. ↵