4 Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc

Thompson Rivers University is located on the unceded and traditional lands of the Secwepémc People, Secwepemcúl’ecw, with this campus being located at Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. The lands where Thompson Rivers University is located was not obtained by consent, nor were the city lands of present-day Kamloops. We learn of Secwépemc hospitality towards the first European explorers to reach the Interior of what they referred to as British Columbia, the “real whites”[1] or the french speaking traders, through the writings of James Teit as he transcribed the Memorial to Sir Wilfred Laurier in 1910.[2] The Indigenous Peoples noted that the “real whites” were guests in their territories, and also that “[w]e could depend on their word, and we trusted and respected them.”[3] They made a distinction from the English-speaking settlers that followed and used the legal system as a tool of dispossession.

This territory has a rich and robust history and unique culture. We must start by acknowledging the beginning, which has allowed us the opportunity to flourish in this territory as guests of the Secwépemc. Their hospitality and trust were taken advantage of. We are studying on stolen native land. While acknowledging the unceded lands of where students receive their legal education is an important part of reconciliation in Canada, it is just a starting point. It is the shared responsibility of TRU Law, and all of us as future lawyers, to become informed of our country’s past and to be aware of the repercussions that Indigenous Peoples continue to face in Canada. It will be a wise and necessary practice to know the territory in which you are living and practicing in when you leave law school, and students are encouraged to always seek out this information.

TRU Law has forged a relationship with Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc that acknowledges the importance of recognition and education for future lawyers. Kamloops, an alliteration of the place name denoting the meeting of the rivers in Secwepemctsín, is uniquely situated in the Interior of British Columbia at the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers. Explorer Simon Fraser named the Thompson River after his fellow explorer, David Thompson, in the early 1800s. In fact, Thompson was exploring the Columbia River watershed to the east and never made it to the Thompson River.[4] Prior to first contact in this area and well before railway construction, the rivers were the highways. The meaning of the name has been explained by local ethnographers Marianne and Ronald Ignace in Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws as follows:

The Secwépemc word for Tḱ’emlúps, usually translated as “confluence” or “meeting of the waters,” has a visually vivid and interesting meaning that gives us clues about past Secwépemc ancestors’ perception of shape and space. The word Tḱ’emlúps derives from the prefix t for “on top of,” plus the root ḱem for “two things coming together at an angle,” plus the lexical suffixes -l/ll for “perpetual” and -ups for “pointed buttocks.” The word invokes the kind of buttock shape that past Secwépemc people saw in the very shape of the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers, still visible from the bird’s-eye view of an airplane or from the lookout on what is now Columbia Street in Kamloops.[5]

The two rivers that divide Kamloops into three large segments are the same waters that supported trading, food sources and inter-tribal relations, amongst others. The north-west segment makes up the current communities of North Shore, Brocklehurst, College Heights, and Westsyde. The southern segment is where TRU campus is located, along with the South Shore, Sahali, Aberdeen, Dufferin, Valleyview, Dallas and Campbell Creek neighbourhoods. Heading east from the confluence of the two rivers, following the headwaters of the South Thompson River, you will find the historic “lakes division”, which remain the caretakers of the area around the Shuswap Lakes, which includes the Secwepémc communities Adams Lake, Neskonlith, Little Shuswap Lake, and Splatsin. This part of the watershed is diverse in its plant growth, leading to a heightened importance of the trade route. The mountains in the lakes district are bountiful in alpine medicines where the lower lands surrounding Tk’emlúps are drier lands, with plenty of sage and soapberries. Northern Secwepémc traditional herbalist Rhona Bowe takes us on a journey through Adams Lake to pick medicines in a forested area.

https://media.tru.ca/id/0_l3hlnkq8?width=608&height=402&playerId=23451100

Traditional Secwepemc herbalist, Rhona Bowe, takes time to explain the medicinal and healing properties of plants in Secwepemc territory. She focuses her discussion on healing trauma, creating tranquility in our lives, and Secwepemc natural laws.

These rivers truly are integral to the community of Kamloops. Not only now, but from time immemorial. Kamloops is unique in this way. TRU Law students are fortunate to learn in this territory which is rich with history, culture, and community. TRU Special Advisor to the President on Indigenous Matters and traditional storyteller, Paul Michel, reminds us that Tk’emlúps is not just a meeting of waters, it is where the waters take us; it is a place where connections are made.[6] Tk’emlúps te Secwepémc Elder and TRU Indigenous Cultural Advisor, Garry Gottfriedson, further develops the definition, indicating that the meeting of the waters is also symbolical of the water that breaks in our mother’s womb when we are born. With this interpretation, Tk’emlúps becomes a place important to birth and growth.

Although the rivers are less relied upon for transportation between communities, there is a shared appreciation for the water between settlers and local Indigenous Peoples alike. With summer temperatures often reaching 35 degrees Celsius, the rivers offer a cool and refreshing place to congregate with friends, family and loved ones. With three major bridges connecting the three sections of Kamloops, the waterways remain integral to the place and meaning of what Kamloops is. During the warmer months, locals can be seen traveling the rivers via kayak, paddle board, dragon boat, river boat, seadoo and tube floating to name a few. It is a place where people congregate, enjoying the beaches with family and friends, and take a plunge to escape the heat, or for traditional bathing practices observed by the Secwepémc Peoples.

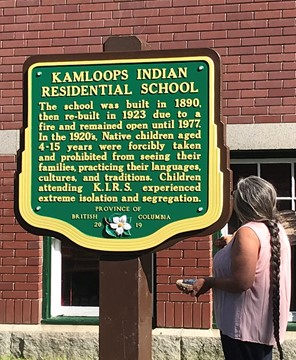

If you visit the north-eastern 1/3 segment of Kamloops, you will find yourself on the current reserve lands of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. Their special events facility, a large open arbour with covered bleacher seating around the perimeter, was designed by the late John Jules, a traditional knowledge keeper from Tk’emlúps. It is located not far from the former Kamloops Indian Residential School (“KIRS”), and hosts the largest competition powwow[7] in Western Canada.[8] Indigenous dancers, singers and spectators travel from across North America to compete, observe and gather for three days. Dancers compete for top cash prizes and flex their physical stamina under the scorching Kamloops summer sun. Singers compete with their drum group for the honour of being named “host drum” the following year. The beat of the drum is amplified through a public address system, calling all to seek and observe. For Indigenous Peoples, the drum ignites their soul—it is the heartbeat of a Nation. Equally important as what happens in the middle of the circle is what happens on the outside of the circle: the artisans’ market. Traditional and non-traditional foods are vended, along with artisan goods such as beadwork, regalia, jewelry and Indigenous fashion. The event is open to the public and often sees upwards to 20,000 visitors over 3 days.[9]

For the other 51 weeks of the year, the special events arbour is used to host other events and gatherings upon request. These events often include National Indigenous People’s Day, Kweseltken Farmers’ and Artisan Market, community meetings, and the odd fashion show. In recent years, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc has opened their special events arbour to host evacuees during the forest fire season.[10] These events and community activities take place in the shadow of the former KIRS, one of few remaining residential school buildings in Canada. The building stands as a stark reminder of the ongoing impact of the residential school system, which constituted genocide. Secwepemc children and children from other nations were forced to attend KIRS tearing their families apart. It is remarkable how Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc has progressed in their battle to overcome this dark history. The resilience of the community is evident in their many celebrations and cultural observances that continue to take place at the Special Events Facility. Their determination and strength as a Nation shines through the shadows of KIRS. At the same time, much honour and respect is owed to the history of the lands that today are celebrated on. They have not always been a happy place for Secwepémc and other Indigenous Peoples.For a period-specific perspective of KIRS, see “The Eyes of Children – life at a residential school”, CBC Digital Archives (25 December 1962), online: <www.cbc.ca>.

In front of the former KIRS is a monument which provides the names of survivors who attended the residential school. KIRS was operational from 1893-1977,[11] meaning that first generation survivors of this school are as young as 50 years old. One of the survivors, the late Mr. Kenneth (Kenny) Jensen, spearheaded, designed and paid for the monument out of his residential school settlement funds. It was a gift to the community to remember those who survived and those who survive only in spirit. TRU Law is fortunate to hear the testimony of Mr. Jensen through his nephew, Ed Jensen, who speaks about his late uncle’s love for his community and the importance of this monument. More recently, it has been utilized as a gathering place of mourning for the 215 unmarked graves that were discovered utilizing ground penetrating radar.[12] We are grateful for Mr. Jensen’s contribution to keeping the story alive, not knowing how important this monument would soon become.

Ed Jensen of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc speaks of his family’s experiences attending the former Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS). As part of his healing journey, Ed’s late Uncle Kenny Jensen solely funded the development and installment of a monument outside the front doors of KIRS to commemorate those who survived and those who did not.

“…[T]he money was a poor substitute for a good life. And the reality was that most of his friends would drink it all away. And it was true. So he was determined to try to make a bit of a difference and he took a big portion of his payout and he dedicated it to that monument at the Residential School.”

https://media.tru.ca/id/0_16qnxamc?width=608&height=402&playerId=23451100

To better understand the impact of KIRS within Secwepemcúl’ecw, it is important to know that there were only 2 residential schools in the territory. Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc is one of 17 communities in Secwepemcúl’ecw. It stretches from the Rocky Mountains in the East, to Castlegar in the South and Williams Lake towards the North. Children came from many communities to attend the Residential School in Kamloops. The closest schools were located outside Williams Lake (Secwepemcúl’ecw) and Lytton (Nlaka’pamux territory), which were 285km and 165km away, respectively. First-hand accounts of attending residential school tells us how children traveled from Nlaka’pamux Territory, Stl’at’imc territory, Okanagan territory, and even Coast Salish Territory to attend the former KIRS.[13] Similarly, children from the Secwepemc Nation traveled to Vancouver to attend residential school on the coast.[14] When we conceptualize the areas and communities that were impacted by the former KIRS, we can then begin to understand the disruption that occurred. Attending residential school meant severing consistent occupation of lands—an incredible interruption to the relationship with and responsibility to tmícw. Marianne and Ronald Ignace describe the impact that has occurred:

In the decades since the late 1920s, ranching and agriculture, logging, mining, urban sprawl, shopping malls, and golf courses have dissected Secwepemcúl’ecw, altering the landscape and stripping the land of its resources at the cost of Secwépemc people in more ways than one.[15]

- Members of the Northwest and Hudson’s Bay Company and French-speaking explorers/traders ("seme7ui7"). ↵

- Shuswap Nation Tribal Council, “The Memorial to Sir Wilfrid Laurier: Commemorating the 100th Anniversary, 1910-2010” (2010), online (pdf): Shuswap Nation <shuswapnation.org/files/2012/09/137543_ShuswapNation_MemorialBro.pdf> [perma.cc/2H3N-YY9E]. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ken Favrholdt, “Kamloops”, Exploring the Fur Trade Routes of North America, ed by Barbara Huck (Winnipeg: Heartland Books, 2000) at 223. ↵

- Marianne Ignace & Ronald E. Ignace, “Chapter 7 Re Stslexemúĺecwems-kucw Secwépemc Sense of Place” Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws Yerí7 re Stsq’ey’s-kucw (Toronto: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 218) at 251. ↵

- To contact Paul Michel, see here (online): Thompson Rivers University <www.tru.ca/indigenous/special-advisor-to-the-president-on-indigenous-matters.html> [perma.cc/5HJ9-HQHX]. ↵

- Competition powwows differ from Traditional powwows. Competition powwows involve judged contest between dancing performers, divided by age, style of dance, gender, and drumming/singing groups. Prize money is awarded at varying amounts. Larger competition powwows, such as Kamloopa, award upwards to $77,000. Traditional powwows, such as TRU Traditional Powwow, does not include contest amongst dancers and singers/drummers, and includes supper provided to all in attendance (spectators, dancers, singers, vendors, etc.). Generally powwows are a more pan-indigenous practice, rather than specific to Secwepemc culture. ↵

- See “Kamloopa Powwow”, Kamloopa Powwow Society, on Facebook. See also “Kamloopa Powwow: The Beating Heart of Kamloops”, Tourism Kamloops (21 July 2017), online: Tourism Kamloops <www.tourismkamloops.com/blog/post/kamloopa-pow-wow-the-beating-heart-of-kamloops/> [perma.cc/2DNN-T9N2]. ↵

- See “Three Kamloops women make enough bannock to feed masses” CBC News (29 July 2015), online: CBC <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kamloops/three-kamloops-women-make-enough-bannock-to-feed-masses-1.3172254> [perma.cc/XSL5-G8LM]. ↵

- Victor Kaisar, “Tk’emlups te Secwpemc a hub of activity with wildfire evacuees” Radio NL (12 July 2021), online: <www.radionl.com/2021/07/12/80745/> [perma.cc/5GAD-BZSP]. ↵

- TRU, then College of the Cariboo, operated out of KIRS in 1977. ↵

- Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, Office of the Chief, (27 May 2021). Remains of Children of Kamloops Residential School Discovered, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, online (pdf): <tkemlups.ca/remains-of-children-of-kamloops-residential-school-discovered/> [perma.cc/68BJ-RU6X]. ↵

- Agnes Jack, ed, Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School, Rev ed (Penticton, BC: Theytus Books, 2006). Nlaka’pamux Territory – Lower Nicola (99km), 164. Stl’at’imc Territory – T’it’q’et [Lillooet] (173km), 188; Xaxli’p [Fountain] (160km), 176. Okanagan Territory – Okanagan Lake (103km), 139. Coast Salish, 184. Far ends of Secwepemc Territory – Williams Lake (289km), 175; Stwecemc [Dog Creek] (229km), 173; Esk’etemc [Alkali Lake] (337km), 184. ↵

- Ibid, at 23. ↵

- Supra note 5 at 492. ↵