10 Genocide

The recent publicity regarding the mass graves at residential schools has shocked many Canadians. The residential school system is one aspect of government policy that violates articles of the Genocide Convention. There is a strong case that the Canadian government committed genocide against Indigenous peoples according to the current standards of international law. That does not mean Canadians should be ashamed of their country, their identity, their culture, or their values. It is important to be critical of the government so we can rectify past wrongs and move forward in a direction where all people are valued.

The Canadian genocide is not limited to the residential school system but includes the totality of colonial policies which in some cases, still exist to this day. For our purposes, we are primarily going to focus on the genocidal aspects of residential school policy, but the status system, reserves, intentional starvation, withholding of life-saving vaccines and medications during a time of widespread disease, dispossession of land, are all elements of genocide. All of these actions were intentional and derive from deeply rooted assumptions of racial superiority. There is a plethora of government documents, laws, and policies that make evident the intent of the Canadian state to commit genocide.

The Genocide Convention

Genocide was first recognized as a crime under international law in 1946, codified in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (The Genocide Convention). The Genocide Convention has been ratified or acceded to by 152 states, but still applies to the states who have not ratified it. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has found the convention to be a matter of general customary international law, or Jus Cogens, meaning it is so fundamental that it applies to countries that have not ratified it. The Genocide Convention consists of 19 articles and was inspired by the thoughts of Raphaël Lemkin.

Raphaël Lemkin was a Jewish-Polish scholar specializing in international criminal law who fled from the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939. The word ‘genocide’ is derived from the Greek words Genos, meaning race or tribe, and Cide, meaning killing. Genocide is targeted towards nationalities and ethnic groups and is distinguished from murder by its systemic nature.[1] Lemkin says,

“It is intended rather to signify a ‘coordinated plan’ of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.”[2]

A ‘coordinated plan’ refers to state policy and is not limited to the systemic killing of a target group, as Lemkin’s conception of genocide is fairly broad. Lemkin observed and studied the wide variety of laws and policies which the Nazi’s implemented before and during the Holocaust, and so his conception of genocide entails things that on their own may not constitute genocide, but when considered in its context they do. For example, the concentration camps of the Holocaust were not built overnight, and there was a variety of laws and policies introduced which de-humanized Jewish people to the point that their treatment was accepted by the general public.

One of the reasons Lemkin’s views of Genocide are wider in scope than the modern-day Genocide Convention is due to the Canadian governments influence during the drafting stages of the convention. Canada took a firm stance that ‘cultural genocide’ should not be admitted and that the Genocide Convention should be limited to the physical destruction of a group. We won’t go over the various arguments made regarding the inclusion of cultural genocide, but it is important to know that cultural genocide is not currently considered genocide per the Genocide Convention. We are not going to be arguing that the government committed cultural genocide, rather, we are going to be arguing that the government of Canada violated articles within the Genocide Convention as it is, and when building a legal case that should be the primary focus.

State Responsibility vs Individual Responsibility

Since the state is an abstract entity and thus cannot act on its own, there may be some questions regarding state responsibility versus individual responsibility. There exists a fairly complicated duality between state responsibility and individual responsibility for the crime of genocide. In 2001, the International Law Commission (ILC) adopted Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts. These articles outline what it takes for a state to be held responsible for international crimes like genocide. The state is responsible for the actions of its officials and organs, and for those who it contracts with. An example of a state being held responsible for genocide is when the ICJ determined that Serbia had violated the Genocide Convention during the Srebrenica Massacre in 1995.[3]

A state can also be held responsible for genocide committed by non-state actors. The Government of Canada paid a third party to operate residential schools and one could expect the government to raise arguments that they are not responsible for what occurred within those schools. While the church organizations operated the schools, the Government of Canada created a vast legal framework which forcibly removed children and put them into the schools.

Articles of the Genocide Convention

Without further delay, let’s get into the specifics of the Genocide Convention. We are not going to go through all 19 Articles of the Genocide Convention and so we will limit the discussion to Article 2, where the definition of genocide is laid out,

“In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”[4]

Although there are various acts that could constitute genocide, there are three common elements among them.

- (i) The persons against whom the act was perpetrated belonged to a particular national, ethnical, racial or religious group;

- (ii) The perpetrator’s intent to destroy, in whole or in part, that national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such;

- (iii) The conduct took place in the context of a manifest pattern of similar conduct directed against that group or was conduct that could itself effect such destruction.[5]

Like any criminal case, we need to make out an Actus Reus and a Mens Rea for each alleged breach of the convention.

Actus Reus

The act of genocide is not limited to murder or immediate execution. Preventing births, forcibly transferring children, causing serious physical or mental harms, or deliberately inflicting conditions that would lead to the destruction of a group are considered acts of genocide. Historically, genocide does not manifest itself in a single act, but a mixture of various actions and policies. A state can indirectly cause genocide by deliberately creating circumstances which leads to things such as starvation, homelessness, and disease. Some acts, such as ‘causing serious bodily or mental harm’ leave room for interpretation. Defining ‘mental harm’ has been described as, “harm amounting to ‘a grave and long-term disadvantage to a person’s ability to lead a normal and constructive life’….”[6] Determining the actus reus is dependent on what article is being infringed and what the factual circumstances are.

Mens Rea

Determining the intent behind genocide is a fact-driven analysis focused on the state’s causal connection with the genocide. Examples of relevant evidence would be government correspondence and records, legislation, cases, and witness testimony. The international criminal tribunal for Rwanda stated in Kayishema:

“Regarding the assessment of the requisite intent, the Trial Chamber acknowledges that it may be difficult to find explicit manifestations of intent by the perpetrators. The perpetrator’s actions, including circumstantial evidence, however may provide sufficient evidence of intent… The Chamber finds that the intent can be inferred either from words or deeds and may be demonstrated by a pattern of purposeful action. In particular, the Chamber considers evidence such as the physical targeting of the group or their property; the use of derogatory language toward members of the targeted group; the weapons employed and the extent of bodily injury; the methodical way of planning, the systematic manner of killing. Furthermore, the number of victims from the group is also important.”[7]

An example of possible evidence can be provided by Duncan Campbell Scott, the former Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, who stated his intentions while pushing for compulsory attendance of residential schools in 1920, stating,

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone … Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.”[8]

Another example could be through the pattern of government behaviours such as forcing Indigenous Peoples into starvation and disease in order to influence them to sign treaties.[9] The intentional starvation of Indigenous Peoples is littered throughout public records, and Sir John A. Macdonald even stated in parliamentary debates:

“It is true that Indians so long as they are fed will not work. I have reason to believe that the agents as a whole, and I am sure it is the case with the Commissioner, are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the brink of starvation to reduce the expense. The Buffalo has disappeared over the past few years. Some few came over this year, and although their arrival relieved the Indians, I was rather sorry…”[10]

Statements made through government reports and correspondence such as those made by Duncan Campbell Scott and Sir John A Macdonald clearly demonstrate an “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”.[11] Another form of evidence showing intent would be the reports and correspondence among government officials which demonstrate that the government was aware of the issues within the residential school system but continued its expansion regardless.

A lawyer responsible for reviewing the Anglican schools, S.H. Blake, wrote to the Minister of the Interior stating, “the appalling number of deaths among the younger children appeals loudly to the guardians of our Indians. In doing nothing to obviate the preventable causes of death, brings the Department within unpleasant nearness to the charge of manslaughter”[12] S.H. Blake continued on to say,

“Many of the schools are utterly inefficient. The teachers are incompetent for the work given them. Some of them should be pupils, in place of pretending to instruct. There has not been progress for years. The schools and equipment are old-fashioned, and are not keeping pace with the requirements of the day. The teachers are unable to interest the little unfortunates committed to their care…. By the mode of treatment employed to-day – the giving of rations, bales of clothing, etc. – the Indian is pauperized and self-reliance and self-respect are done away with. The Indian is educated into a humiliating state of dependence and higher aspirations are quenched.” [13]

The Minister of the Interior at the time, Frank Oliver, wrote a brief reply where he stated:

“I think that the religious education is very important, much more important than any technical education that can possibly be given…. I do not consider that the certificate of the teacher is material. His influence for good over the pupil is very much more important than any certificate…. I regret that I am not able to deal more fully with the important questions which you raise… I am very glad to see the interest in which you take in the improvement of the Indians, and also the fairness of your point of view…”[14] The comments made by S.H. Blake were made before attendance at the schools became compulsory, so there is evidence to show the government knew about the situation within the schools but continued to expand and force children into them anyway. Let’s turn to the schools more specifically and apply the facts to the Genocide Convention.

Article 2(b) Causing Serious Bodily or Mental Harm to Members of the Group

When applying Article 2(b) to the facts we have to contemplate what constitutes serious bodily or mental harm. The question of what constitutes serious harm has been brought up in various cases and has been otherwise scrutinized for being vague. The drafters of the genocide convention chose the wording they did because it “permitted international courts and tribunals to ensure a progressive understanding of the crime: one that captures acts of sexual violence and the forced displacement of populations, and acts over a broad spectrum of time.”[15] The definition is largely determined by the context and cannot be determined by an exhaustive list of actions.[16]

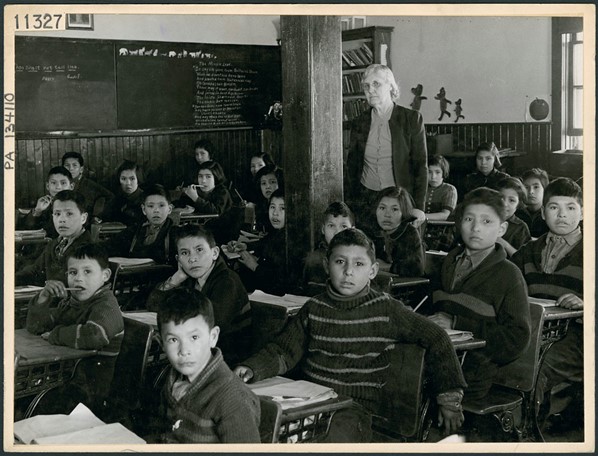

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) established that residential schools caused a “grave and long-term disadvantage to a person’s ability to lead a normal and constructive life”.[17] On reserves and in residential schools, Indigenous Peoples suffered from both preventable and treatable illnesses that because of the conditions, led to lifelong injuries or death. Students who attended residential schools told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission about the lack of food and medical care in the report, The Survivors Speak. Some students have claimed that for serious diseases, such as tuberculosis, students were either placed into isolation and given food but no actual medical treatment, while the more severe cases would be sent home shortly before their deaths.[18]

According to survivors, the days consisted of religious indoctrination, hard labour, harsh punishments for speaking Indigenous languages and contacting family members, under-heated schools, barrack-style living arrangements, chronic malnutrition, unfit food, and witnessing other children being beaten.[19] One of the reasons the food was unfit or non-existent was in part because of government corruption. Edgar Dewdney, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories between 1879 and 1888, had formed personal financial relationships with the firm where the government received large amounts of food from, I.G. Baker.[20] Not only was the food of poor quality but there were allegedly manipulations and connivances among I.G. Baker and the Indian agents who allocated food supplies to people on reserves.[21] Similar problems occurred during the construction of the schools themselves. The government provided grants to build the schools but did not follow through with any sort of inspections. The buildings were poorly constructed which led to many problems, including negatively impacting the health of the students.[22]

In addition to harsh day-to-day lives, children faced sexual and physical assault at the hands of not only the staff but other students as well.[23] As previously mentioned through the comments of Frank Oliver, the federal government had no standards for who was certified to teach in the schools, providing pedophiles with easy access to children, a problem which in some instances the government of Canada along with the United Church has been held legally responsible for by the Supreme Court of Canada.[24] The international court presiding in Akeyasu stated that the infliction of sexual abuse and rape constitutes serious bodily and mental harm.

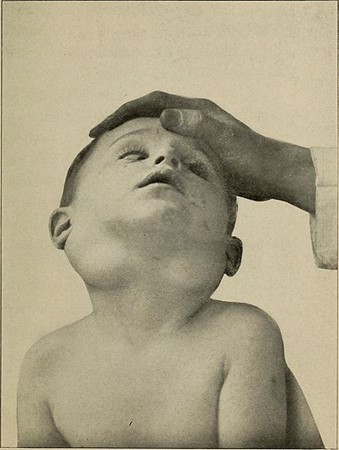

The claims made by survivors can often be corroborated with government reports, and in at least one instance, the government conducted nutritional experiments on malnourished children.[25] The main cause of death in residential schools was disease. The disease was running rampant amongst an Indigenous population who had not built up a similar level of tolerance to the diseases European settlers carried.[26] While attempts were made by some altruistic Europeans to help mitigate the spread of disease among Indigenous populations, the epidemics were significantly exacerbated for First Nations because of government policy that was focused on fiscal restraint and withholding supports to create leverage in treaty negotiations.[27]

The most impactful disease at the time was tuberculosis, and the government was well aware of the extremely disproportionate rates of disease in the schools compared to the general population. Dr. Peter Bryce was hired by the Department of Indian Affairs to report about the health conditions of the schools in 1907. In the 1907 report, Dr. Bryce spoke at length about the prevalence of tuberculosis in schools. He also noted high rates of mortality of students shortly after leaving the schools. Furthermore, he stated that he had a hard time obtaining attendance records from the schools, as many did not comply with his requests. In his report, he noted:

“…7 percent are sick or in poor health and 24 percent are reported dead. But a close analysis of some of the returns reveals an intimate relationship between the health of the pupils while in the school and that of their early death subsequent to discharge”. He goes on to state that “It suffices for us to know, however, that of a total of 1,537 pupils reported upon nearly 25 percent are dead, of one school with an absolutely accurate statement, 69 percent of ex-pupils are dead”[28]

Dr. Bryce’s notes suggest that many students died shortly after being released from the residential school, which means the schools likely sent the children away when they were terminally ill in order to avoid dealing with the dead body and to defer responsibility. Dr. Peter Bryce also makes it very clear that the conditions in the schools exacerbated the spread of disease and other illnesses. He noted in his report, the lack of proper ventilation and ability to regulate temperatures in the schools (due to underfunding) contributed to the spread of various illnesses. Dr. Bryce remarked that he was surprised given the conditions that there were not more deaths in the schools. He stated in his report:

“It is apparent that general ill health from the continued inspiration of an air of increasing foulness is inevitable; but when sometimes consumptive pupils and, very frequently, others with discharging scrofulous glands, are present to add an infective quality to the atmosphere, we have created a situation so dangerous to health that I was often surprised that the results were not even worse than they have been shown statistically to be.”[29]

Dr. Bryce’s 1922 report was a much more scathing document as it was produced after he left his official position with the government. In that report he stated:

“This story should have been written years ago and then given to the public; but in my oath of office as a Civil Servant swore that “without authority on that behalf, I shall not disclose or make known any matter or thing which comes to my knowledge by reason of my employment as Chief Medical Inspector of Indian Affairs.” Today I am free to speak, having been retired from the Civil Service and so am in a position to write the sequel to the story.”[30]

In the 1922 report, he acknowledged that the recommendations of the previous report were never published. The recommendations, which he included in the 1922 report, included a recommendation that “the health interests of the pupils be guarded by a proper medical inspection and that the local physicians be encouraged through the provision at each school of fresh air methods in the care and treatment of cases of tuberculosis”.[31]

Dr. Bryce lambasted Duncan Campbell Scott’s active opposition to the various medical reports that were being done each year, including Scott’s opposition to the opinions of medical professionals and experts.[32] Scott prevented Dr. Bryce’s report from being “a matter of critical discussion” at an annual meeting of the National Tuberculosis Association. Dr. Bryce also points out the substantial difference in cost attributed to tuberculosis patients in a city like Ottawa compared to funding for Indigenous Peoples. Dr. Bryce noted:

“Thus we find a sum of only $10.000 (SIC) has been annually placed in the estimates to control tuberculosis amongst 105,000 Indians scattered over Canada in over 300 bands, while the City of Ottawa, with about the same population and having three general hospitals spent thereon $342,860.54 in 1919 of which $33,364.70 is devoted to tuberculous patients alone.”[33]

He goes on to talk about the “criminal disregard” for the Indigenous Peoples that the government signed treaties to protect. He concludes his report by stating “It is indeed pitiable that during the thirteen years since then this trail of disease and death has gone on almost unchecked by any serious efforts on the part of the Department of Indian Affairs…”.[34] Not only had the rates of disease within the schools not been addressed, but Duncan Campbell Scott terminated the position of medical inspector within the department and negotiated an agreement to expand the residential school system.[35]

Article 2(c) Deliberately Inflicting on the Group Conditions of Life Calculated to Bring About its Physical Destruction in Whole or in Part.

The questions we must ask when addressing Article 2(c) is what technically constitutes ‘physical destruction’, and what exactly are the ‘conditions of life’ that bring it about. There has been extensive discussion in academia since the drafting of the convention about the scope of Article 2(c). According to Adi Radhakrishnan in, An Inherent Right to Health: Reviving Article 2(c) of the Genocide Convention, “(t)he final version of Article II(c) in the Genocide Convention was the result of deliberate efforts to avoid defining genocide too narrowly, fearing the inadvertent exclusion of a form or method of genocide”. During the drafting of the article, various states debated the language of the “conditions of life” that reflected concerns unique to each state. It was also contemplated that an absence of action (such as an absence of adequate medical care and food) constituted an instrument of genocide. Ultimately, it was determined that “conditions of life” be kept broad so as to not exclude one method or another. Radhakrishnan summarized the debates as following:

To resolve the debates, the final version combined three propositions that arose during discussions: it 1) emphasized a directness of acts of genocide, 2) that groups can be destroyed by the targeting of its members, and 3) that the group can be destroyed without the death of its members. Although many First Nations people have died as a result of Canada’s colonial laws and policy, the death of a group’s members is not required for genocide to occur. This was affirmed in the International Criminal Tribunal’s trial chamber decision of Prosecutor v. Stakić:

“Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part” under subparagraph (c) does not require proof of a result. The acts envisaged by this sub-paragraph include, but are not limited to, methods of destruction apart from direct killings such as subjecting the group to a subsistence diet, systematic expulsion from homes and denial of the right to medical services. Also included is the creation of circumstances that or physical exertion.”[36]

A subsistence diet, the systematic expulsion from homes, and the denial of the right to medical services were all a part of the Canadian government’s policy towards Indigenous Peoples, and specifically in the residential school system. The entire purpose of the residential school system was to bring about the conditions of life which would destroy Indigenous Peoples as a group. There does not need to be proof of a result in order to show that genocide has occurred but lasting impacts to the group can be statistically analyzed. For example, according to the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, First Nations people are six times more likely than the general population to suffer alcohol-related deaths and more than three times more likely to suffer drug-induced deaths. Indigenous peoples make up about four and a half percent of the total population of Canada but make up around thirty-one percent of the prison population. Similarly, children in child welfare custody are about fifty percent Indigenous, even though they make up about seven percent of the total youth population. In addition to this, the overall suicide rate amongst First Nation communities is about twice that of the total Canadian population. For Inuit, the suicide rate is even higher: six to eleven times than the rate for the general population. Aboriginal youth between the ages of ten and twenty-nine who are living on reserves are five to six times more likely to die by suicide than non-Aboriginal youth.[37]

Article 2(e) Forcibly Transferring Children of the Group to Another Group.

The forcible transfer of children from one group to another group is considered to be genocide if the transfer results in serious bodily and mental harm and is conducted with the intent to destroy the group in whole or in part.[38] By this point, we have established that the residential school system resulted in serious bodily and mental harm and that the intention underlying the system was to destroy the group in whole or in part.

The question then is whether the use of force was used to transfer children into the schools. The use of force to remove children from their families as defined by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in a case referred to as Akayesu. The Trial Chambers says, “…as in the case of measures intended to prevent births, the objective is not only to sanction a direct act of forcible physical transfer but also to sanction acts of threats or trauma which would lead to the forcible transfer of children.”[39] The point the tribunal is making is that the use of force is not limited to directly taking a child through violence, but that indirect methods would count as well. An example of an indirect method would be the threat of imprisonment for those who failed to comply through the passing of legislation.

In Canada, Indigenous children were forcibly removed in a multitude of ways, including the implementation of laws that threatened to punish people with fines and imprisonment if children did not obey attendance laws. In 1894, amendments to the Indian Act made it mandatory to send Indigenous children to residential schools and that was enforced by Indian agents with the help of the RCMP.[40] According to The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports, as well as internal reports conducted by the RCMP, children were physically removed and taken to the schools by Indian Agents, Church Officials, and the RCMP.[41]

The purpose of this case analysis is to show that the residential school system would be considered genocide by modern legal standards. The concept of genocide goes further than the legal definition, as there are various philosophical and historical definitions. Groups of people have been persecuted since the beginning of human societies, and those persecutions are documented in some of the oldest known writings. While international law is a relatively new development, the moral significance of genocide has been appreciated for centuries.

Today we can look back and connect many of our modern concepts to ancient Greek philosophers, but it is important to note that the Hellenization of Judea came with the persecution of Judaism. Jewish religious practices were banned, and gymnasiums were built to ‘educate’ people on the Greek ways of living. While education has likely changed most of our lives for the better, it has also been used throughout history as a destructive force.

Education is powerful, and that is why it is so important that we educate ourselves about genocide and the history of Canada. We as individuals must also look deeper, past the tuition fees and the grades. We must evaluate what drives humanity to commit such horrendous acts. It has happened throughout history, it happens now, and it will happen in the future. How can we as legal professionals make sure that our society treats people with dignity and respect going forward? It starts with education, but it ends with individuals changing their perspectives on what it means to exist within a society, what it means to appreciate our cultures, while also valuing others. No one is perfect. No culture is perfect.

Canada could do better in many regards. We can all do better in many regards. We need to take our ability to learn and use it to educate others on these issues. We cannot rely on the institutions to fix us, because they have and will continue to let us down. If we fail to promote education in a manner that is rooted in individual kindness, positivity, and love, we will fall victim to our past mistakes. The intent of this case analysis is not to make you feel shame, but to help you learn about what it means to be a human being. At the end of the day, educational institutions can only take us so far, and we as individuals need to take more responsibility for our behaviors.

- Tamara Starblanket, Suffer the Little Children : Genocide, Indigenous Nations and the Canadian State (Atlanta, Georgia: Clarity Press, 2018) at 39-40. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Bosnia and Herzegovina v Yugoslavia, Preliminary Objections, Judgment, ICJ Reports 1996, p. 595 ↵

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 9 December 1948, UNTS Vol 78 Article 2, (Entered into force 12 January 1951). ↵

- Elements of Crimes, Summary Report, ICC, 2011. ↵

- Prosecutor v. Krajišnik, 27 September 2006, Judgement, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, case no. IT-00-39-T. ↵

- Prosecutor v. Kayishema, 21 May 1999, Judgement, ICTR, Case No. ICTR-95-1-T at 93 ↵

- National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, volume 6810, file 470-2-3, volume 7, pp. 55 ↵

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life, 1st ed. (Regina Saskatchewan: U of R Press 2013) at 114-126. ↵

- Canada. Parliament. House of Commons Debates, Official Report, Volume 12 (Ottawa: Queens Printer and Controller of Stationary, 1882). ↵

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 9 December 1948, UNTS Vol 78 Article 2, (Entered into force 12 January 1951). ↵

- Anglican Archives, MSCC, Series 2-14, Special Indian Committee, 1905-1910, S.H.Blake to the Hon. Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, To the Members of the Board of Management of the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada, by The Hon. S.H. Blake, K.C., at 21. ↵

- Ibid, at 21 ↵

- Ibid, at 22 ↵

- Nema Milaninia, Understanding Serious Bodily or Mental Harm as an Act of Genocide, Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, Vol. 51, Issue 5, At 1417 ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Final Report (Winnipeg, 2015) ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak (Winnipeg 2015), at 177-181 [The Survivors Speak]. ↵

- Starblanket, supra note 1 at 60. ↵

- Supra 9, at 115 ↵

- Ibid at 137 ↵

- John S. Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 2nd ed. (Winnipeg Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 2017) at page 79-30 ↵

- The Survivors Speak, supra note 31. ↵

- Blackwater v. Plint, [2005] 3 S.C.R. 3, 2005 SCC ↵

- Ian Mosby, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942–1952” (2013) 46-91 Social History, 145-172. ↵

- Supra note 9 at 99-158 ↵

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life, 1st ed. (Regina Saskatchewan: U of R Press 2013) at p. 99-158 ↵

- Canada, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Report on the Indian Residential Schools of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1907) at 18. ↵

- Ibid at 19. ↵

- Peter H. Bryce, The Story of a National Crime: Being an Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada; The Wards of the Nation, our Allies in the Revolutionary War, our Brothers-in-Arms in the Great War (Ottawa, James, Hope and Sons, 1922) at p.15. <archive.org/details/storyofnationalc00brycuoft/page/n5/mode/2up> [perma.cc/H25S-TS3W]. ↵

- Ibid at 4. ↵

- Ibid at 5. ↵

- Ibid at p.15. <archive.org/details/storyofnationalc00brycuoft/page/n5/mode/2up> [perma.cc/H25S-TS3W].at 13. ↵

- Ibid at p.15. <archive.org/details/storyofnationalc00brycuoft/page/n5/mode/2up> [perma.cc/H25S-TS3W].at 14. ↵

- Indian Act, 1920 s.10(1) ↵

- Prosecutor v. Stakić, 31 July 2003, Judgement, ICTY, Case No. IT-97-24-T at para 517. ↵

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation at 108-109 (Winnipeg, 2015). ↵

- Starblanket, Supra note 1 at 55-58 ↵

- Prosecutor v. Akayesu, 2 September 1998, Judgement, ICTR, Case No. ICTR-96-4-T at 509. ↵

- An Act to Further Amend the Indian Act, S.C. 1894, c. 32, s. 11. (found at https://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aanc-inac/R5-158-2-1978-eng.pdf) ↵

- Marcel-Eugene LeBeuf, The Role of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police During the Indian Residential School System (Ottawa: Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2011). ↵