8 A Brief Historical Narrative of the Residential School System

The residential school system is part of a wider system of policy aimed at, what officials at the time called, “civilizing” and eventually assimilating Indigenous peoples. It is important to underscore the involvement of various church organizations in the operation of residential schools. Religion was historically a major part of political life because religious institutions had jurisdiction over morality. The notion that Indigenous Peoples needed to be “educated” in the first place largely stems from dogmatic Christian perspectives operating on assumptions of ideological superiority.[1] One of the main methods of “civilizing” Indigenous Peoples was to christianize them, separating them from their traditional cultural beliefs and values. Governments would rationalize and reinforce the churches’ claim over the human mind through the production of reports and the creation of laws that aimed to deteriorate the Indigenous person’s sense of being in a systemic way.

The earliest residential schools date back to as early as the 1600’s and were operated by Catholic missionaries in conjunction with the French government.[2] The earlier schools had a hard time recruiting and retaining students because Indigenous communities were self-sufficient and did not see the need to send their children to religious schools.[3] Indigenous Peoples were more than capable trade partners and at times even fought common enemies alongside European settlers. The Department of Indian Affairs was created in 1755 as part of the military branch to help coordinate alliances with various First Nations.[4] Settlers in large part relied upon Indigenous peoples and respected their independence, evident through the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which recognized Indigenous rights and title.

As the power dynamic shifted so too did the policy towards Indigenous peoples; they stopped becoming allies and trade partners and started to become a ‘problem’. To fix the problem, the Anglican church waged an ideological war against Indigenous Peoples, opening the first residential school in Canada, the Mohawk Institute, in 1831.[5] By 1845, the Bagot Commission Report had recommended to the government a federal system of residential schools and emphasized the value of taking Indigenous children away from their parents for the purposes of “civilization”.[6] The Indian Affairs Superintendent stated in 1847:

It is found that you cannot govern yourselves. And if left to be guided by your own judgement, you will never be better off than you are at the present; and your children will ever remain in ignorance. It has therefore been determined, that your children shall be sent to Schools, where they will forget their Indian habits and be instructed in all the necessary arts of civilized life, and become one with your white brethren.[7]

The government passed the Gradual Civilization Act in 1857 which served as a mechanism offering enfranchisement to ‘educated’ Indigenous persons. Enfranchisement was voluntary and so only one person used it initially.[8] During Confederation the federal government became responsible for the education of Indigenous Peoples, side skirting the Royal Proclamation and instituting a much more aggressive assimilation strategy.

In 1879 Prime Minister John A. Macdonald commissioned Nicholas Flood Davin to look at the boarding schools in the USA and produce a report, informally known as the Davin Report.[9] Davin describes a residential school system as the principal feature of a policy of “aggressive civilization”.[10] The report outlines what we now think of as the residential school system, and the Indian Act was amended in 1884 to put the system into action.

“11. The Governor in Council may make regulations, which shall have the force of law, for the committal by justices or Indian agents of children of Indian blood under the age of sixteen years, to such industrial school or boarding school, there to be kept, cared for and educated for a period not extending beyond the time at which such children shall reach the age of eighteen years.”[11]

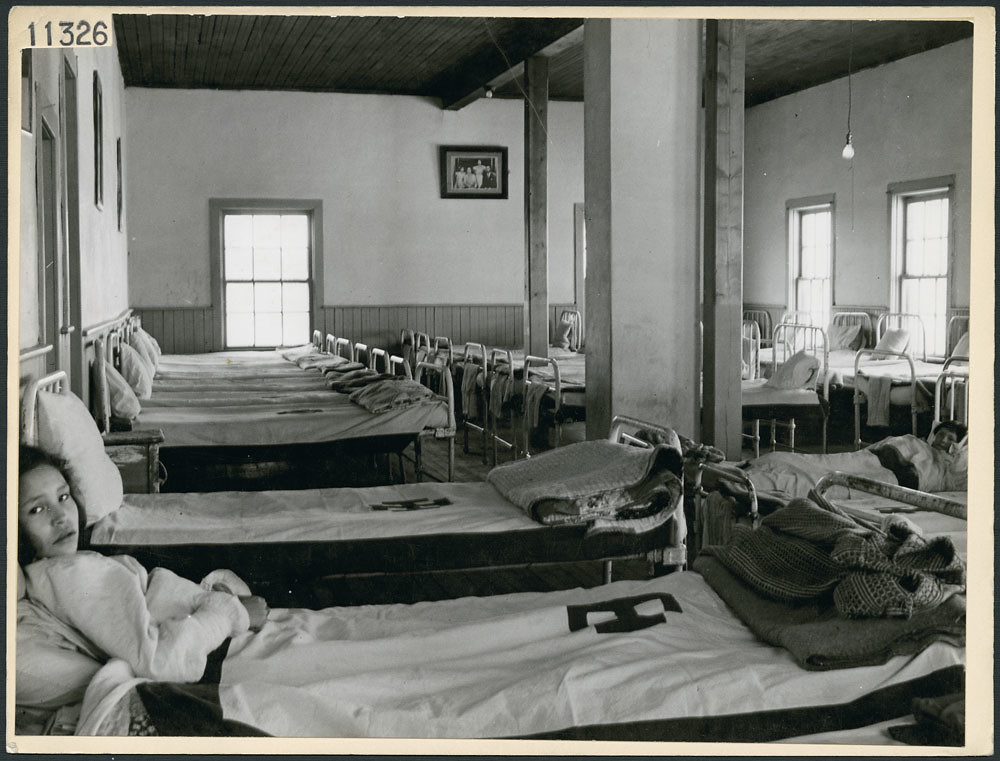

The government made a deal with various Church organizations in 1892 to have them operate the schools at a fixed per-student rate which led to overcrowding. The system was severely underfunded, so the students were expected to work even though they were malnourished and often sick.[12] At the turn of the 20th century, it became apparent that the conditions at the schools led to an epidemic of tuberculosis.

Dr. Peter Bryce was a health official who was hired by Indian Affairs to produce a report on the health of the students at the residential schools, where he reported that 24% of the students had died from tuberculosis.[13] He claimed the cause was poor ventilation in the schools and a poor standard of care. Dr. Bryce would conduct similar yearly reports until George Duncan Scott became Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs in 1913. The government relieved Dr. Bryce of his duties as they had no intention of acting upon the reports. At the time health care funding granted to citizens in Ottawa alone was about three times higher than to all First Nations in Canada.[14]

While attending residential schools did not become legally mandatory until amendments were made to the Indian Act in 1920, the government used other policies to force children into the schools. Due to policies such as the implementation of the Indian reserve system, Indigenous communities faced extremely high mortality rates. Starvation and disease were utilized by the federal government to weaken Indigenous communities.[15] When an Indian agent would come along offering to take the children where they would be fed, clothed, and taken care of, it was hard to say no. When people started realizing the children were being subjected to abuse, malnutrition, disease, and death, they resisted sending their kids to the schools which in turn led the government to make attendance mandatory.

More than 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children attended the church-run schools between their establishment in the 1870s and the closure of the last school in the mid-1990s. While the schools were starting to be phased out in the 1960s the underlying goal of assimilation was not. In 1951, the Indian Act was amended to give the provinces control over Indigenous child welfare. The provinces saw Indigenous communities that were struggling with the consequences of an abusive residential school system and decided to start taking children from their families and putting them in mostly non-Indigenous homes. In 1951, Indigenous children made up about 1% of children in care, by the mid-1960s that number had jumped to over 33%.[16]This mass removal of children and infants from their families is referred to as the “Sixties Scoop”.

Based on historical records and correspondence throughout pre-and post-confederate Canada, it is evident that the Canadian government was intent on using the residential school system as a method of ethnic cleansing, and can be strongly argued to meet the philosophical and legal thresholds of genocide.[17] The final report on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women does not shy away from the term and argues it is still going on today in other ways.[18] Looking at the law historically provides insight into what ideas and beliefs informed the legal structures of our society. Unfortunately, deep-seated racism permeates through the policy governing Indigenous peoples.

- John S. Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2017) ↵

- J.R. Miller, "Troubled Legacy: A History of native Residential Schools" (2003), 66:2, Sask.L.Rev. ↵

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, Residential Schools in Canada, online: The Canadian Encyclopedia <www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools> [perma.cc/5SKD-92TK]. ↵

- Canada, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, A History of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, (Quebec: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada) online (pdf): Government of Canada <www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ/STAGING/texte-text/ap_htmc_inaclivr_1314920729809_eng.pdf> [perma.cc/9SML-ZK7E]. ↵

- Supra note 3. ↵

- Canada, Annual Report, 1880, Department of the Interior. "Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds". Nicholas Flood Davin, 1879 ↵

- Canada, Minutes of the General council of Indian Chiefs and Principal Men, Orillia, Lake Simcoe Narrows, (Montreal: Canada Gazette, 1846) ↵

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, Gradual Civilization Act, Online: The Canadian Encyclopedia <www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/gradual-civilization-act#:~:text=European%20settler%20society.-,Description,land%20ownership%20and%20wealth%20accumulation> [perma.cc/3ZS8-YK92]. ↵

- Supra note 3 ↵

- Derek G Smith, “The "Policy of Aggressive Civilization" and Projects of Governance in Roman Catholic Industrial Schools for Native Peoples in Canada, 1870-95” (2001), 43:2, Anthropologica, Canadian Anthropology Society) ↵

- Indian Act. R. S., c. 43, s. 1. 1884 ↵

- James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009) at 135. ↵

- Peter Henderson Bryce, Report on the Indian schools of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau; 1907. ↵

- Travis Hay, Cindy Blackstock & Michael Kirlew, “Dr. Peter Bryce (1853–1932): whistleblower on residential schools.” (2020), 192:9, CMAJ E223, online: Canadian Medical Association <www.cmaj.ca/content/192/9/E223> [perma.cc/GN3W-B6PD]. ↵

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina, 2014) ↵

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, The Sixties Scoop, online: The Canadian Encyclopedia <www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sixties-scoop> [perma.cc/L8P8-ZKSH]. ↵

- Tamara Starblanket, Suffer the Little Children: Genocide, Indigenous Nations and the Canadian State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2018) ↵

- Canada, National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019). Volume 1A. ↵